The usher said it was “away up there.” How right he was. The Amalie Arena had provided a sturdy railing for those in the nosebleed seats. We threaded our way up the perilous incline, dodging the akimbo arms and knees of those sitting at aisle ends. We fell into our assigned seats. The arena’s ceiling ended three rows back. All around were fellow plebes, too thrifty to pop for the hundreds of dollars needed to sit among the glitterati close to the stage on the floor below.

My heart thumped, partially from the ascent, but also from the stress of two hours’ crawling centimeter-by-centimeter through Tampa rush hour traffic. A light would turn green a block ahead, we would feel a burst of elation. No one moved! Hadn’t the idiots ahead of us seen the light change? The light would turn back to red, and we would lurch forward as two cars at the head of our column made it, squeezed across the intersection like toothpaste from a tube.

With fifteen thousand others, we were at the hockey stadium to hear Andrea Bocelli. I wondered. How many people were both an opera fan and a hockey fan? If Andrea delivered a spectacular glissando, would fans throw hats on the stage? Program notes? Opera glasses? Elvis had panties and brassieres thrown at him.

The crowd in our section dressed casually in jeans, shorts, and skirts. They looked like they had stepped out for dinner at Carrabba’s. In the case of My Life’s Editor and myself, we wore informal threads, were careful not to spill mustard from the Cuban sandwich we were sharing. On the big bucks main floor below there were stacked heels, glittering red dresses, and tuxes suitable for a head waiter at Donatello’s.

When I was a child, my classical music was The Stars and Stripes Forever, played by the army post band on the parade ground. My mother did have a thing for Enrico Caruso when she was a girl, but that did not translate to her barbarian children. When I was in seventh grade, Mrs. Miller played Peter and the Wolf and The Grand Canyon Suite for us, explaining how the bassoon was the grandfather in Peter and how the percussion instruments made the clippity-clop of the burros in Grand Canyon. I focused on flicking spit wads at the back of Eddie Altuna’s head.

I come by classical music and opera through marriage. At four years old, My Life’s Editor was taken to a performance of La Traviata with the Cleveland Orchestra. She was entranced. She cried when Violetta collapsed dead on a bed at the end. She gasped when Violetta came out on the stage to take her bows. Wait, didn’t that lady just die!? Years later the Met came to Cleveland and put on Aida with actual horses and camels among the sopranos. That clinched the deal for herself.

I am grateful for the English captions (surtitles) above the stage at operas. “La Donna e Mobile” in Rigoletto, for instance, translates as “The woman is fickle,” eliminating the possibility she hails from a city on the Gulf of America. This aria, by the way, is hypocritical coming from the Duke, who is a cad and a bounder and seduces the beautimous Gilda, Rigoletto’s daughter.

Even better would be a display on a Jumbotron with stats, like at a ball game:

Singer: Rudolfo Andante

- Height: 5’7”

- Weight: 250 lbs

- Position: Tenor

- Vocal Range: 2 Octaves

- Gestures: Righthanded

- Born: Padua, Italy 1998

There were no surtitles at the Bocelli concert. We were on our own.

The lights dimmed and a hundred-person choir filed into elevated seats on the stage, followed by an equally large orchestra in front of them. The whole kit and kaboodle had to be in Charleston the next day and Miami the day after that. We wondered if the entourage – choir, orchestra, singers, lighting and electronic techs – travelled together like the Ringling Brothers circus. Would violinists consent to travel in the same bus as tuba players? How would they handle laundry?

The first violin player, the concertmaster, stood up and played an “A” on his violin, which set the orchestra to tuning up like an aviary full of irritated birds. The conductor arrived on stage and shook the hand of the concertmaster as if the two had never met. The string instrument crowd tapped their bows on their music stands in approval, sounding like bamboo stalks rattling in a breeze. The conductor stood before his music stand, straightened his shoulders, waved his baton, and the orchestra burst into Bocelli’s opening piece, like Aaron Judge’s walk-up song as he steps out of the on-deck circle.

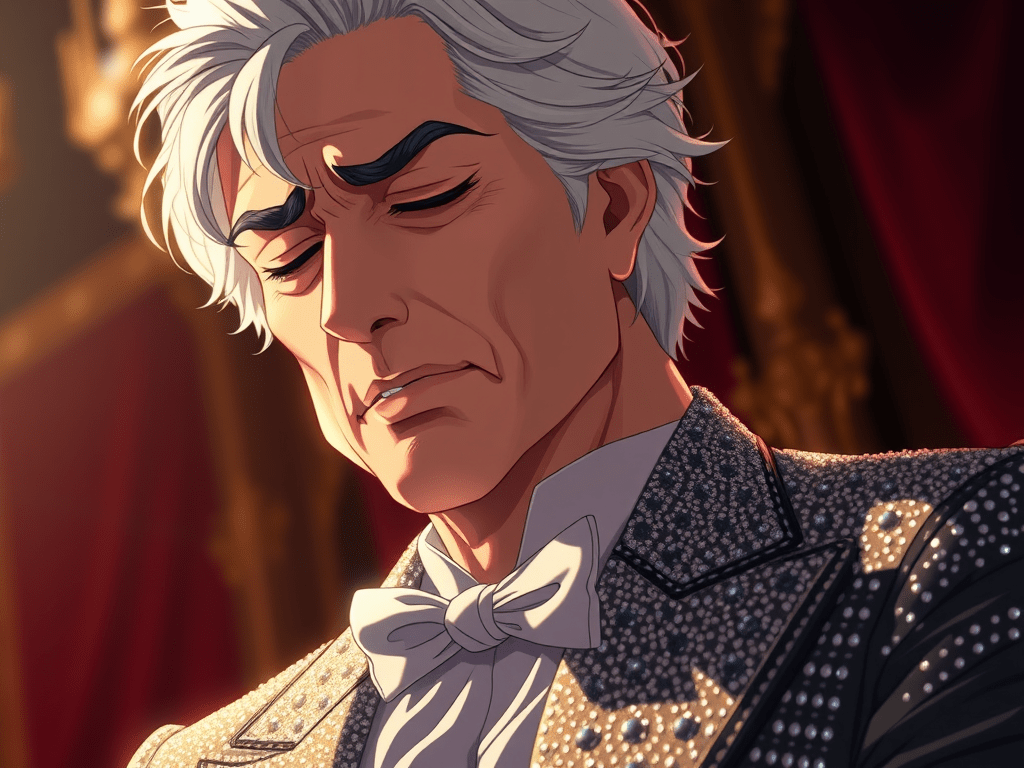

Bocelli ascended the stage gracefully, silver hair setting off a tanned face, his figure slim and erect in a glittering tuxedo jacket. The audience roared. At his elbow was a gorgeous woman who led him up to perform and then would retrieve him to rest his pipes in between arias. He had a harem of sleek sopranos performing solos while he was offstage. I flashed on James Brown and his serial stage exits. He would swoon, worn out by his performance, his cape swirling around him, and stagger toward the wings, supported by one of his Famous Flames, the audience screaming for more. When he reached the edge of the curtain, he would pause dramatically, turn, miraculously reinvigorated, and sweep back, basking in more adoration. So it was with Andrea Bocelli.

As he sang, his hooded eyes made it seem as if we were watching a man at prayer. Hockey fans and music mavens stood and cheered as the final note of his evening’s performance faded into the ether of the Amalie. We bravoed ourselves hoarse. Tampa traffic, nosebleed seats, and cold Cubans did not matter at all.

This is just WONDERFUL, Marshall. Thank you!SteveSteven M. Seibert850.321.9051

LikeLike

Thanks for the Bravo 👏

LikeLike

Thanks for the Bravo 👏

LikeLike

Thanks for the Bravo 👏

LikeLike